I was in the FBO shack with my instructor, discussing regulations as part of the ground instruction requirement for my flight review. A short, muscular man entered the building, his nearly new composite airplane shining outside in the cold morning sun. Behind the FBO counter another CFI, the glass-cockpit aircrafts local factory-authorized instructor, stood in greeting. I overhead their exchange: “Hi, doc,” he smiled. “How was your flight down last night?” The first real cold snap of autumn was upon us, and the skies had been cloudy the night before. The glass-cockpit pilot almost bragged in reply: “We had ice all the way, down to about 3000 feet. But I broke out on the approach. There was about a quarter inch on the wings and tail when we landed.” The pilot actually laughed. “We made it home all right.” The instructor replied: “Yeah, you dont really need to worry about it until you get half an inch or more.” Yikes! Good Judgment

The suggestion is strong that, not only was it okay to fly an airplane with no real ice protection in night IMC while accumulating ice, but that it would be acceptable to do it again so long as the situation was not twice as bad (half an inch of ice as opposed to one-quarter) next time. Such reinforcement is extremely persuasive if the other pilot is high-time (from the viewpoint of the listener), an airline or Commercial pilot, an instructor or someone seen as speaking with the authority of the airplane manufacturer.

“Good judgment” is hard to define. I know that being hit with demerits for “bad judgment” was the death knell for me or my compatriots in Air Force Officer Training School. Bad judgment seemed to be loosely defined as doing something embarrassing, contrary to existing rules and norms, or flat-out dumb.

“Good judgment,” then, might be defined as “doing things in accordance with existing standards, where the outcome is positive, easily defendable with minimal explanation and, in most instances, never requires explanation at all.” As pilots, we should strive not only to arrive without injury or damage to the airplane, but in a manner where a safe landing was never an issue. As the Practical Test Standards put it, “the successful outcome is never seriously in doubt.”

Complacency

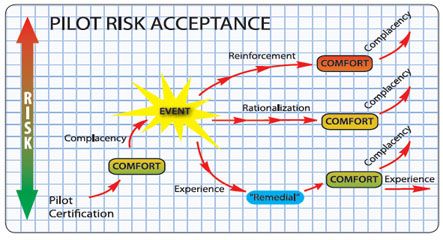

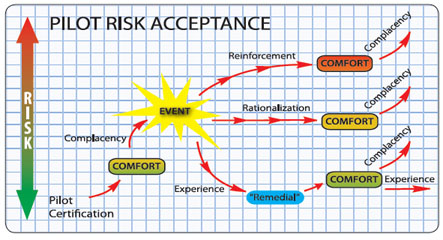

Most pilots dont actively train beyond this point, and complacency starts to set in. After all, having a couple hundred hours sounds like a lot of experience to a pilot just starting out. Complacency disguises itself as confidence, and tends to cause pilots to accept higher and higher levels of risk.

Then one day something happens. It might be an icing encounter or getting too close to a thunderstorm; it could be an electrical failure at night or an inadvertent IMC penetration. A “significant aviation event” is a dangerous risk-management turning point that can go one of three ways:

Experience and possibly fear cause the pilot to reassess risk exposure. He/she may overreact and force a very low risk acceptance level-“Ill never fly at night again,” etc. The pilot enters an informal “remedial” period when he/she regains confidence, possibly takes some additional training, and restores at least some comfort albeit at a low risk tolerance that may artificially limit his/her flying. From there it once more becomes a battle between experience and complacency to determine how the pilot will accept risk over time. This risk acceptance path is the genesis of the “no old, bold pilots” credo.

Simple survival of the event allows the pilot to rationalize the behavior. “I ducked a few feet under the glideslope and saw the runway” becomes “If I fly it a couple dots low on glideslope Ill make it every time.” The pilots comfort level rises to a higher acceptance of risk. Further complacency threatens to increase risk exposure to even more unacceptable levels. The next “significant aviation event” might not be so survivable.

Worst-case is when decision-making in the “significant aviation event” is reinforced by peer groups or especially persons in authority. Local FBO lounges, hangar-flying sessions and Internet chat rooms are full of reinforcement of basically unacceptable behavior. Knowing that “thunderstorm avoidance is for less-experienced pilots” prompts repeat flirtations with circumstances that led to the first event, and exposure to even greater levels of risk because “I know more than most pilots; therefore I can handle it.”

You might dispute some of the assumptions of this unscientific model, but the overall lesson is that pilots need to constantly assess their risk acceptance, honestly assess the risk-management impact of in-flight events and consider whether their current comfort level is truly acceptable for themselves and their passengers.

Capability vs. Experience

In each case a large percentage of the pilot population was making a huge leap in aircraft capability. Often in these cases, and suggested in the Cirrus mishap rate, the pilot simply does not have the experience to make good decisions when taking advantage of the vast capability of the new design. The answer is training and operation well within the flight envelope until greater experience improves scenario-specific judgment and permits flight closer to the maximum capability of the airplane.

For instance, if youre new to a glass cockpit airplane you might consider flying in visual conditions only until you have, say, 25 hours in type and undisputed command of the cockpit technology.

Denial and Compensation

Wh

From the NTSB: The Cessna Model 337 Skymaster was cleared to takeoff, and according to a tower controller, got airborne approximately 1000 feet down the runway. After another 500 feet or so, it pitched up to between an estimated 30-45 degrees, then leveled off at an estimated 150-200 feet agl. Approximately five seconds later, the wings rocked up and down and the airplane drifted north of the runway. The airplane rolled nose- and left-wing low, then appeared to level off before impacting the ground.

Earlier that day, the accident pilot flew the recently purchased airplane on three separate flights; a pilot-rated passenger later reported the airplane pitched up aggressively during liftoff. The passenger reported the elevator trim setting was in the correct range for takeoff.

Lets review: A pilot takes delivery of a newly purchased airplane and makes three short flights that he apparently feels suffice as a checkout. The airplane exhibits unusual control reactions and the last flight ends in a hard landing. Yet the airplane pitches dangerously on at least three takeoffs and one landing before the new owner, who does not have the pitch excursions investigated, finally stalls and plunges to his death. Did the pilot exhibit good judgment? Or was he denying that a problem existed and attempting to compensate, or work around, the control difficulty?

Its hard to predict exactly how well respond to conditions and temptations once we make a “go” decision. The trick to aeronautical judgment, then, is to know why we make poor decisions, and what we can do to improve judgment.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.